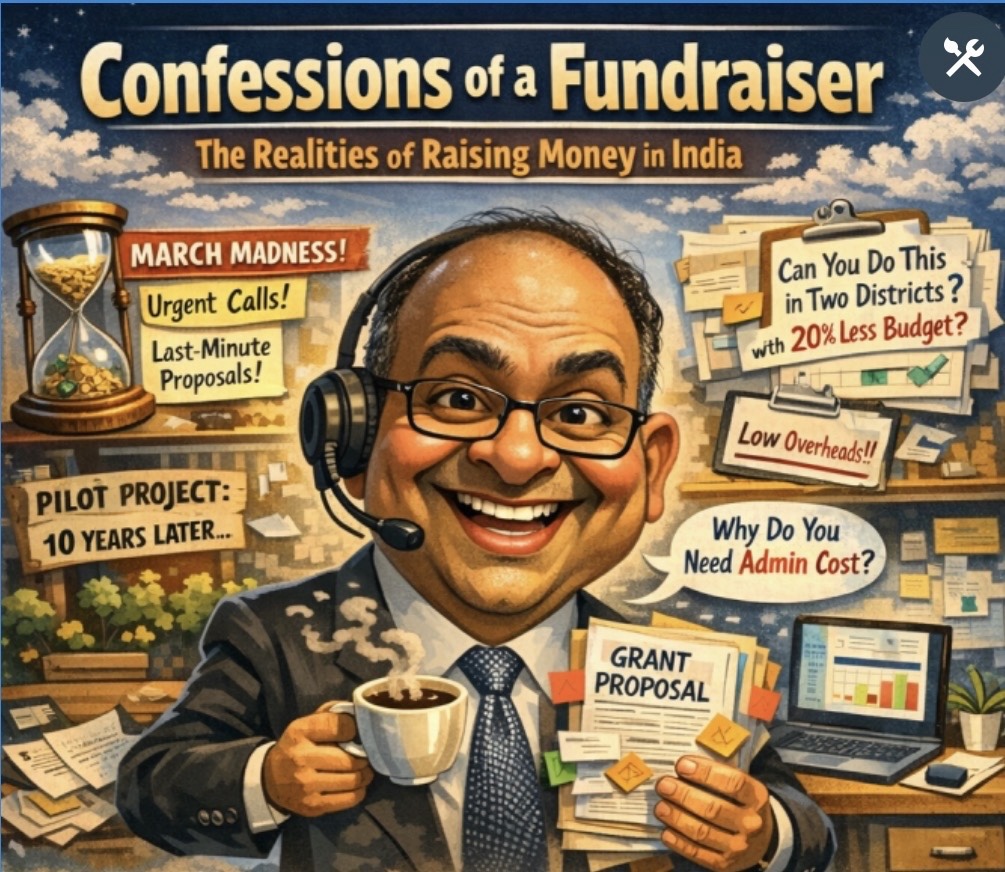

Confessions of a Fundraiser

February 2, 2026 Leave a comment

By a Head of Development, who has been there, done that.

I have spent a good part of my career raising funds for livelihoods and entrepreneurship, environmental sustainability, and digital inclusion. These are kinds of work that everyone agrees are deeply important, and expects to be delivered at miraculous speed, near-zero overheads, and with measurable transformation visible by the next board meeting! Over the years, I have learned that in India’s funding universe, March is not just a month but a mood, where phone calls are returned with unprecedented urgency, proposals are rediscovered with fresh enthusiasm, and sustainability plans are requested even before the first grant tranche has cleared. I have learnt to speak fluently about empowerment while explaining, with equal conviction, why empowerment requires trainers, coordinators, field activities, local transport, and a field office. I have learnt that pilots can run for a decade and still be called pilots, that social impact is expected to be both transformative and inexpensive, and that the most common expression of donor admiration is, ‘This is excellent work. Can you replicate in two districts with 20% less budget?’ And yet, I have also learnt that when trust is built patiently, and partnerships are approached as shared responsibility rather than transactional funding, the system does work, unevenly, imperfectly, but often just in time.

If you ever want to test your emotional resilience, professional patience, and metaphysical belief in destiny, try becoming a fundraiser for social impact in India. Not as a hobby or a phase in life, but as a full-time, salaried, KPI-driven profession where your success is measured in crores raised, relationships sustained, and hopes renewed, often all before lunch. Fundraising in India is not a job; it is a personality type. It is a slow-burning spiritual practice. It is also, on some days, a contact sport.

Most fundraisers do not grow up dreaming of this life. No child has ever said, ‘When I grow up, I want to write concept notes, follow up politely seven times, and still be told the CSR budget has already been exhausted for this year.’ Fundraisers are usually people who joined the development sector with good intentions and then stayed because they discovered a rare combination of optimism, masochism, and an above-average tolerance for ambiguity. In India, fundraising also requires fluency in multiple dialects, not linguistic ones, but donor dialects. You must speak CSR, philanthropy, family office, multilateral, HNI, trust, and the particularly tricky language known as ‘let’s take this offline.’

Every fundraising journey begins with a proposal that is equal parts strategy and speculative fiction. A document that must be simultaneously visionary and realistic, innovative yet ‘scalable,’ rooted in community voice and at the same time aligned to the donor’s thematic priorities for the current financial year. The proposal must do many things at once: ‘Solve poverty + empower women + be sustainable by the third year + align with SDGs (preferably all of them) + cost exactly the amount the funder has available + have low overheads but world-class MEL.’ You will spend weeks refining language, perfecting logframes, and polishing budgets, only to be asked in the first meeting, ‘Can you explain this in two lines?’ You will smile, compress your knowledge of years of community work into a sentence, and remind yourself that clarity is a virtue, even when it hurts.

Sooner or later, every fundraiser in India faces the great philosophical question of our time: Why do you need staff to run a project? Recently, another question got added to my great list when a funder asked me, ‘Why do you need field offices to implement a community-based high-touch project?’ Mind you, I managed a straight-faced answer, without any smirk or sarcasm, even though I cursed the day I decided to be a fundraiser.

Admin costs are a suspicious category in the minds of Indian donors. They include dangerous items like salaries, rent, electricity, and internet, none of which, apparently, contribute to impact. As a fundraiser, you become adept at explaining that projects do not run on goodwill and sunlight alone. That field teams do not teleport. That data does not collect itself. You learn to say ‘lean but adequate,’ ‘efficient yet ethical,’ and ‘value for money’ with full sincerity. I have even attempted some humour at times on the negotiation tables, saying, ‘Without admin costs, the project will still exist, but just as an idea.’ Results vary post such statements.

What I have understood is that fundraising in India is less about money and more about relationships. Money is merely the by-product of trust built over years, conversations, coffees, conferences, and carefully worded WhatsApp messages. I have learnt that a ‘quick call’ can last an hour or more, a ‘small grant’ can require six levels of approvals and may take two years; silence doesn’t mean rejection (or acceptance); words from leadership are golden, but if you don’t have that in writing, you are screwed. The fundraiser’s greatest skill is not writing; it is patience. You patiently wait for responses, for board meetings, for the next quarter, for the funder who loved your work but is noncommittal. You wait with optimism, and dignified reminders, gentle ones every couple of weeks.

Then comes the project visit by the funder, usually by some of their board members and senior leadership. Often, they bring moments of high drama along with it. For the donor, it is a glimpse into our community-connect and implementation efficiency. For a fundraiser, it often turns into a logistical marathon involving vehicles, weather, community leaders, beneficiaries, translators, photographers, and a strong hope that nothing goes wrong. In all such visits, we fundraisers pray to some invisible power that the roads are navigable, community meetings start on time, funder’s visibility is primed, and no one asks an unplanned question about funding gaps. If all goes well, the funder says, ‘This is so impactful.’ You nod, beaming. You make a mental note to follow up in three days. At the beginning of my fundraising career in India two decades ago, I often ended up being shocked by the variety of demands by donor representatives visiting project sites. Thanks to the information age, the visiting representatives nowadays are well informed and often invested in social change.

Fundraisers also live at the intersection of data and dignity, translating lived experience into metrics without stripping it of meaning.Indian donors want data and stories, and at times, even at the cost of losing the bigger picture. You learn to convert human change into numbers without losing the soul of the work. You say things like, ‘4025 women trained’, and then you add, ‘Meet Sunita, who now earns independently and negotiates at home.’ You know that neither is sufficient alone, and the narrative together, they might just unlock the next tranche.

How can I forget the ultimate sword of big NO! Rejection is a constant companion of us fundraisers, like a dark shadow. Sometimes polite, sometimes vague, and sometimes dressed up as ‘great work, but not this year.’ You learn not to take it personally, mostly. You also learn that today’s rejection can be tomorrow’s opportunity, because India’s funding ecosystem is small, relational, and cyclical. The donor who said no last year may say yes next year, after changing jobs, priorities, or perspectives. So you keep the door open, always.

Fundraising is emotional labour. You hold hope for communities, for organisations, for teams whose salaries depend on your ability to convince someone that change is worth investing in. You are optimistic on behalf of others, even on days you feel tired. You absorb anxiety, translate urgency, and project confidence. You celebrate quietly when funds come through, and cushion disappointment when they don’t. You are expected to be resilient, persuasive, strategic, and endlessly positive. No one tells you this in job descriptions.

And yet, despite the follow-ups, the spreadsheets, the rejections, the ‘please reduce your budget by 15-20%,’ and often ending up becoming a football between the funder and the grantee management, we choose to stay. Because once in a while, a funder truly listens. Once in a while, a partnership feels equal. Once in a while, funding aligns perfectly with need, timing, and trust. And in those moments, you remember why fundraising matters. Because social impact does not scale on passion alone. It scales on resources, relationships, and people willing to ask again and again for something better.

So here’s to the fundraisers in India: The translators. The bridge-builders. The professional optimists. May your proposals be read, your follow-ups answered, and your impact always exceed your budgets. And may you never lose your sense of humour. Wishing you strong coffee, timely approvals, and generous funders, today and always.

May the force be with you!

(Disclaimer: The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not purport to reflect the views or opinions of any organisation, foundation, CSR, non-profit or others. This is a humorous attempt, and not angst, and certainly no disrespect for donors and funders of social impact.)

(Cover image is generated using AI)