Digital Bihar, Inclusive Growth

June 4, 2025 Leave a comment

Bihar has a rich historical and cultural heritage and is one of the most populous states in India, with a population exceeding 13 crores[i] and a predominantly rural population. The state faces several challenges in digital literacy, access to technology, digital inclusion, economic development, and equitable growth. However, recent initiatives in e-governance, education, and entrepreneurship hold much promise and potential for contributing towards India’s vision of a digitally empowered society.

Digital literacy remains a significant challenge, with rates below 30% (national average 38% for household digital literacy[ii]), as reported by Ideas for India[iii]. Bihar’s low digital literacy follows its socio-economic conditions, including high poverty rates[iv] (33.76% below the poverty line and 51.91% multidimensional poverty as of 2021) and limited access to digital devices. Rural areas, which hold 75% of the state’s population face challenges due to inadequate infrastructure and low literacy levels. The state’s overall literacy rate, as per 2017 data, stands at 70.9%[v], with rural areas at 69.5% and urban areas at 83.1%. Female literacy, at 60.5%, is significantly lower than male literacy at 79.7%, further complicating efforts to bridge the digital divide.

The digital divide in Bihar is a significant barrier to inclusive development. According to the India Inequality Report 2022 by Oxfam India[vi], Bihar has the lowest internet penetration among Indian states and a wide urban-rural digital divide, with only 31% of rural residents using the internet compared to 67% in urban areas. This rural-urban divide is further worsened by socio-economic disparities.

- Internet Penetration: Bihar ranks among the states with the lowest internet penetration in India. The rural-urban divide is stark — while urban centers like Patna are better connected, most rural areas still suffer from slow or no internet access.

- Device Access: Among the poorest 20% of households, only 2.7% have access to a computer, and 8.9% have internet facilities.

- Gender Gap: Women are 15% less likely to own a mobile phone and 33% less likely to use mobile internet, with India having the widest gender gap in the Asia-Pacific at 40.4%. In many households, men have primary access to mobile devices and internet usage. Women, especially in conservative or low-income families, are often excluded from digital usage.

- Electricity Issues: Frequent power cuts and unreliable electricity supply further hinder the consistent use of digital devices in rural areas.

- Language Barriers: Most digital content is in English or Hindi, which becomes a constraint for people who speak regional dialects such as Bhojpuri, Maithili, or Magahi.

The digital divide affects important sectors like education, healthcare, and finance. For example, in 2017-18 only 9% of students enrolled had access to a computer with internet for education[vii]. Initiatives like BharatNet, aimed at providing rural connectivity, have been unable to deliver effective outcomes. Bihar is one of the focus states for the Digital India Programme, but execution lags due to infrastructural challenges.

In recent years, Bihar has made significant strides in leveraging digital services in improving governance and public service delivery. The National Informatics Center (NIC) Bihar State Centre, established in 1988, plays a central role in this transformation (https://bihar.nic.in/). It supports departments such as revenue, district administration, rural development, finance, agriculture, employment, election, social welfare, and food and civil supplies with IT solutions. The ServicePlus portal is a key platform, offering services like certificate issuance and case status checks, though rural access remains a hurdle, particularly for marginalized communities, requiring better infrastructure and awareness. These barriers require continued investment in training and infrastructure to ensure widespread digital literacy. Common Service Centres (CSCs) and Vasudha Kendra are crucial for providing government and private services to rural and remote areas in Bihar, enhancing digital inclusion and accessibility. However, they are not enough to cater to the growing needs of the rural population. People travel to block towns and larger villages, to access even basic G2C services, indicating the lack of any nearby facility.

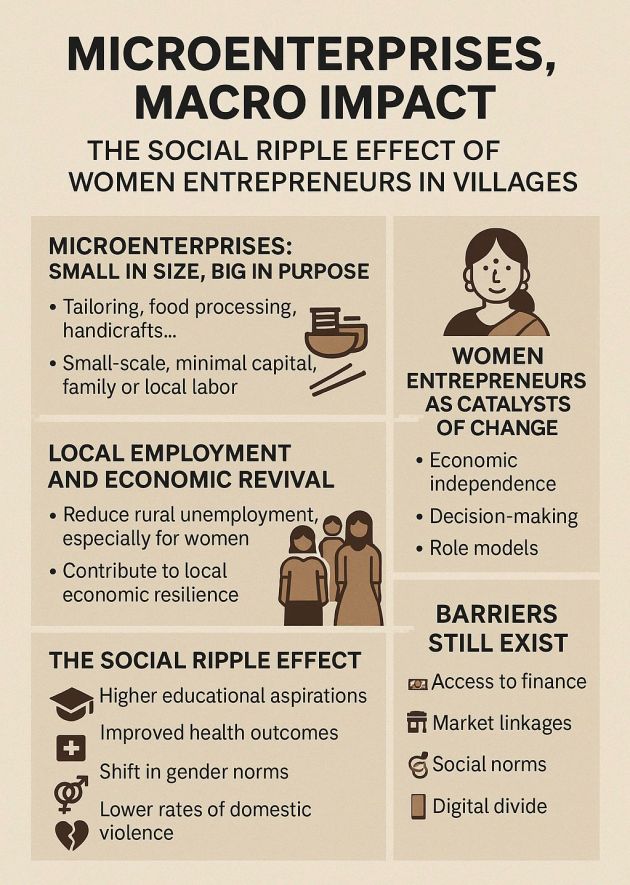

For bridging the digital divide, a digital entrepreneurship program in 500 villages from five districts, viz., Darbhanga, Samastipur, Patna, Nalanda, and Gaya was launched in 2023. Bihar is witnessing a transformative wave of service accessibility led by women digital entrepreneurs. These trailblazing women are not only redefining the entrepreneurial landscape but also catalyzing inclusive development across the state. This initiative provides capacity building and mentoring in digital skills, customer service, entrepreneurship development, financial support and resources, and digital tools to women from socially and economically disadvantaged communities, helping them become successful rural digital entrepreneurs and build a Digital Entrepreneurship Ecosystem. This holistic approach equips them to offer essential digital services in their communities, such as facilitating access to government schemes, online education, and digital financial services. From being computer illiterate to providing a host of over 70+ digital services, these digital entrepreneurs have come a long way only within 9 months of their venture-start in their villages. Some of their services include a large suite of G2C services, design & printing services, online form filling, Banking services, and Mobile payments, among several others. They have also been cross-selling and diversified in selling non-digital products. In this short period, they have already served over 250,000 rural customers (around 40% female customers), and is expected that as their businesses mature, they will be providing digital services to over 7.5 lakh population. Apart from making digital services easily accessible at the village level, they are generating income and securing their futures, with some of them steadily earning upwards of INR25,000 monthly. This program is not only bridging the digital divide but also promoting economic security and social equity, local inclusive economic development, gender equality, awareness, and opening opportunities for skills development.

While government efforts are underway, a coordinated approach involving public-private partnerships, local community engagement, and targeted digital inclusion programs is essential. Programs like these need to be scaled up across the state covering the entire 8,387 Gram Panchayats for bridging the digital divide and contributing significantly to Bihar’s and India’s digital economy.

(All views are personal)

[i] Bihar caste survey conducted in 2023

[ii] https://www.ibef.org/blogs/m-governance-revolution-mobile-apps-empowering-indian-citizens

[iii] https://www.ideasforindia.in/topics/governance/the-digital-dream-upskilling-india-for-the-future.html

[iv] https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/bihar-has-most-poor-people-in-india-niti-aayog/article37698673.ece

[v] https://www.thehinducentre.com/resources/article30980071.ece/binary/KI_Education_75th_Final_compressed.pdf#page=68

[vi] https://www.oxfamindia.org/knowledgehub/workingpaper/india-inequality-report-2022-digital-divide

[vii] https://www.theindiaforum.in/forum/bihar-turns-its-back-school-education