Microenterprises, Macro Impact: The transformative social impact by rural women entrepreneurs

May 21, 2025 2 Comments

Across India’s villages, a quieter and powerful transformation is unfolding, led by women entrepreneurs building microenterprises that are changing not just their lives but also contributing towards local prosperity.

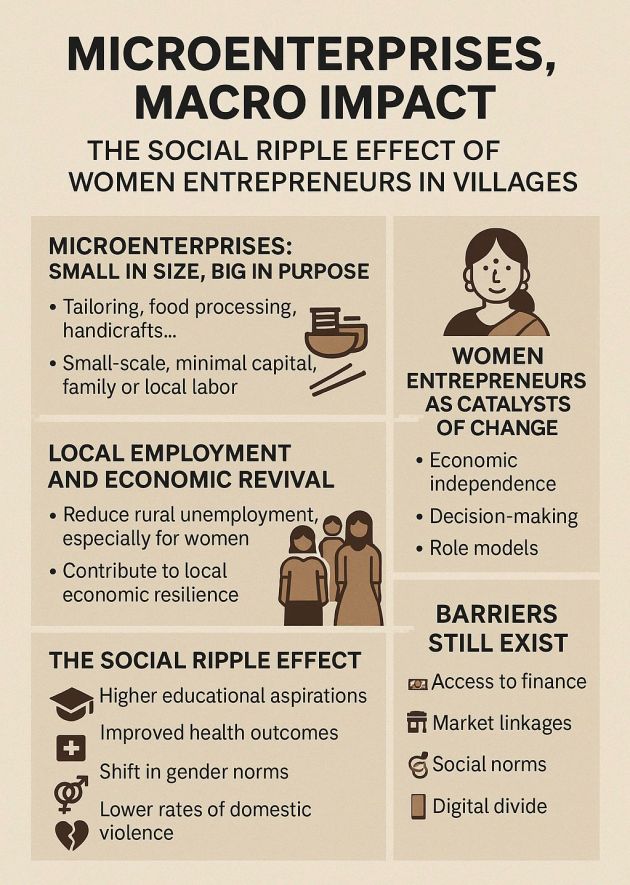

In rural India, microenterprises (and many a time, even termed as nanoenterprises) are typically small-scale and often home-based ventures. These include tailoring shops, grocery stores, food processing units, poultry farms, handloom or handicraft businesses, among many others. They usually operate with minimal capital, often under INR 1 lakh, and rely on family support systems. While these businesses may appear modest on the surface, they’re laying the foundation for grassroots economic resilience and social transformation.

When a woman in a village starts a business, she’s not just earning an income, she’s stepping into a position of agency. She becomes a decision-maker, a provider, and importantly, a role model.

In Jharkhand, Shashi, a determined and resilient woman, has become a role model of empowerment in her village of Kura. With knowledge, financial and device support, she started her Digital Business, which became a hub of convenience and accessibility for people in her village and neighbouring villages. Her journey as a digital entrepreneur empowered her and gave her the agency to make a meaningful contribution to her community. Today, she’s also a Mukhiya (village head) and fondly known as “Digital Mukhiya”, continuing to be the voice of women’s empowerment.

Microenterprises help address the rural employment gap, especially for women who often can’t migrate or work outside the home due to social norms and family responsibilities. These businesses absorb local labour, retain economic value in the village, and reduce dependence on urban employment.

In Assam, Mintai’s Jacquard Handloom Weaving business now employs 3-4 local women who were previously unemployed. They earn and save, and for the first time, imagine futures that include good education for their children or owning a business.

This kind of bottom-up economic activity contributes to local economic resilience, the ability of communities to survive and thrive even during external shocks. The social impact generated by women entrepreneurs is profound. This often translates into higher educational aspirations for children, especially girls staying and completing their school education; increased income leading to better nutrition, access to healthcare and sanitation leading to improved health outcomes; acceptance and shift in gender norms; and financial independence gives women negotiating power within households leading to lower rates of domestic violence.

Despite their success, rural women entrepreneurs continue to face systemic challenges like, (a) collateral requirements and credit histories disqualify many from accessing formal loans, (b) getting products to larger and fairer markets remains a logistical challenge, (c) stifling social norms due to resistance from family or community, (d) accessing business education to develop ‘aptitude’ matching their entrepreneurial ‘attitude’, and ( e) digital divide due to limited access to smartphones and digital tools. While schemes like Stand-Up India and MUDRA loans have made progress, implementation gaps persist.

Rural women’s microenterprises are not side projects. They are economic engines, social change-makers, and community stabilizers. When one woman is empowered to start a business, a ripple begins, touching families, uplifting communities, and reshaping rural India from the ground up.

If you’re a policymaker, social investor, donor, or even just a storyteller, your support can help expand that ripple into a wave and finally a movement of economic security and resilience.

(All views are personal)

(Cover image generated using AI)

#Stand-upIndia #LetsDoMore