How sustainable is Sustainability?

September 15, 2025 Leave a comment

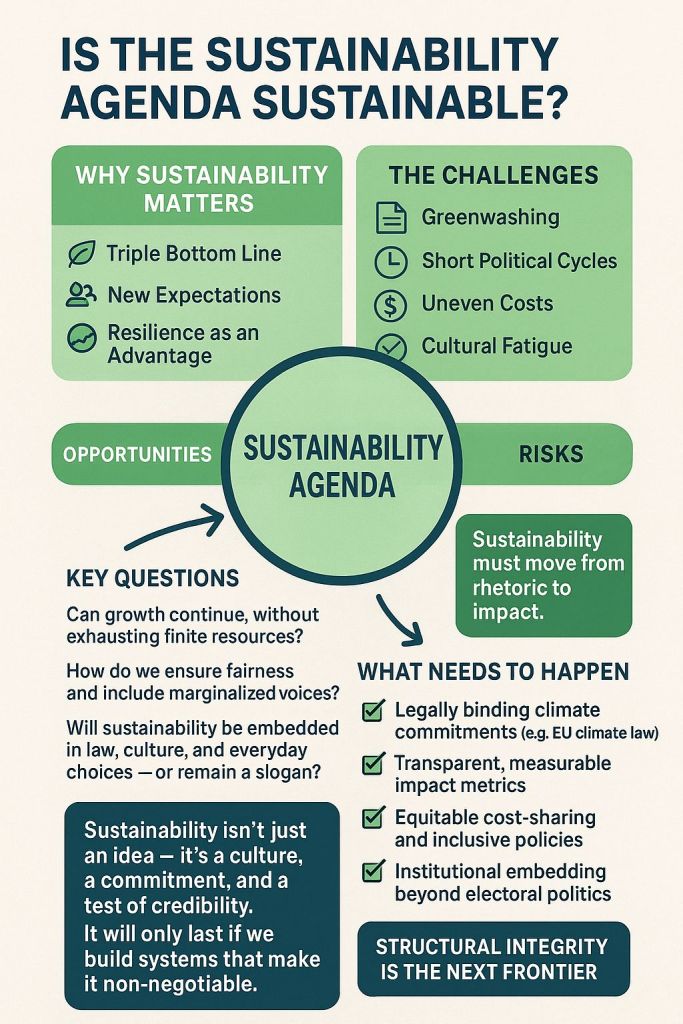

Few words have travelled as far and wide in recent decades as “sustainability”, and has certainly surpassed another overused (in recent past) term ‘social capital’ in usage! It has become synonymous with progress in corporate boardrooms, multilateral summits, government policies, NGO goals, and grassroots movements alike. From ESG scorecards to climate pledges, from net-zero roadmaps to community-led conservation, the language of sustainability has become universal. Every government strategy, corporate report, and grassroots initiative seems anchored in the promise of a more sustainable future. Yet beneath this consensus lies a paradoxical and uncomfortable question: ‘is the sustainability agenda itself sustainable?’

The modern sustainability agenda rests on a powerful proposition that economic growth, social equity, and environmental stewardship can be reconciled. This “triple bottom line” has mobilized unprecedented investment in renewable energy, green finance, and inclusive business models. It has inspired younger generations to demand more from institutions. And it has reframed long-term resilience as a competitive advantage, not a trade-off. But the very breadth of the agenda also makes it fragile. Sustainability risks becoming a catch-all phrase, diluted by overuse and co-opted for public relations more than systemic change. “Greenwashing” scandals, short political cycles, and the uneven costs of climate transitions all threaten to erode public trust. Without credibility and consistency, the agenda risks collapsing under its own ambition.

Sustainability requires commitments that extend far beyond the horizon of electoral politics. Yet in many countries, climate targets or ESG mandates are vulnerable to reversal when governments change. Contrast this with the European Union’s legally binding climate law, a structural safeguard that makes sustainability less of a political preference and more of a shared contract. Unless sustainability is institutionally embedded, it remains hostage to short sightedness.

Green growth advocates argue that economies can decouple prosperity from resource use. The rapid expansion of renewable energy, circular economy models, and impact investing provide evidence of possibility. Yet sceptics highlight that global consumption continues to outpace planetary boundaries. The sustainability agenda will endure only if it reconciles with the fundamental question of growth Vs limits. Can infinite growth coexist with finite resources?

No agenda, however well-intentioned, survives if it is perceived as unjust. For sustainability to be sustainable, it must embody fairness that includes redistributing costs, creating inclusive opportunities, and acknowledging diverse voices, particularly from the Global South. Social justice and legitimacy must go hand in hand.

Ultimately, sustainability is not just a strategy, it is a cultural shift. The more it embeds in consumer choices, organizational values, and educational systems, the harder it becomes to reverse. Yet cultural fatigue is real. When “sustainability” is reduced to a buzzword on every product label, development projects, and corporate brochure, it risks losing meaning. The agenda must therefore move from rhetoric to demonstrable impact, measured transparently and communicated honestly.

The sustainability agenda is both fragile and resilient. Fragile because it depends on long-term alignment across politics, markets, and societies, an alignment often in short supply. Resilient because it has transcended niche environmentalism to become a mainstream expectation that governments and corporations cannot ignore.

Its endurance will depend not on visionary statements but on institutional embedding, equitable policies, and a relentless focus on credibility. At its best, sustainability can serve as the organising principle of a new social contract, aligning business, government, and citizens toward long-term collective wellbeing. Sustainability will only be sustainable if it delivers, not someday, but today.

The next frontier is not about asking companies, governments, or communities to “do more” on sustainability. It is about demanding structural integrity – mechanisms, institutions, and accountability frameworks that ensure sustainability survives political shifts, economic pressures, and cultural fatigue.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not purport to reflect the views or opinions of any organization, foundation, CSR, non-profit or others.