Measuring Entrepreneurial Attitude

June 23, 2025 Leave a comment

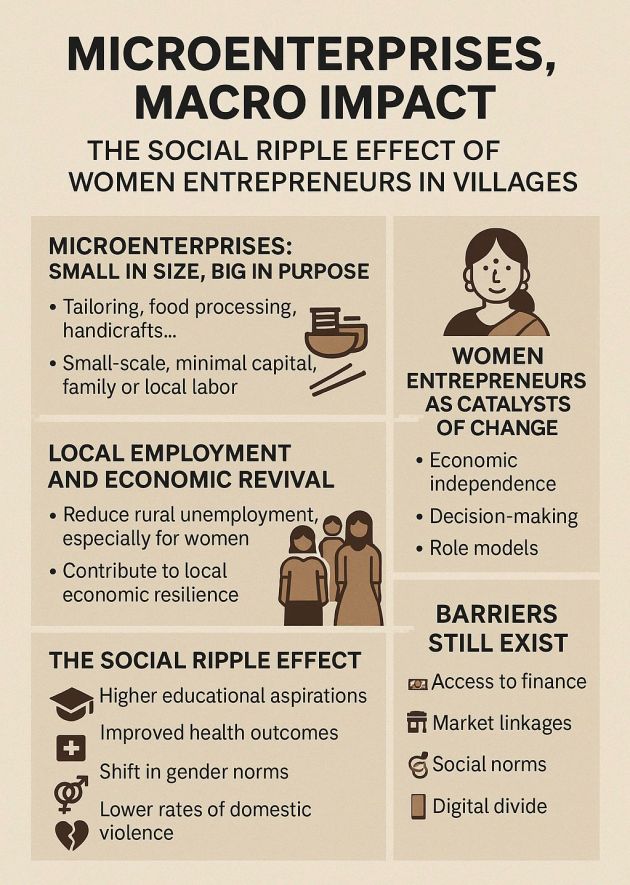

In India’s rural economy, entrepreneurship has emerged not merely as a means of livelihood but as a powerful solution for social and economic transformation. While skills development programs like Skill India, Startup India, and Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushalya Yojana, and numerous capacity-building workshops by NGOs have made significant progress in imparting entrepreneurial aptitude, the more elusive and often underappreciated dimension is entrepreneurial attitude. This inner compass and entrepreneurial mindset, shaped by motivation and initiative, resilience, risk-taking ability, adaptability, and opportunity identification, is what ultimately sustains a venture through uncertainty.

Entrepreneurial aptitude is teachable. It usually comprises financial literacy, business planning, marketing, and digital skills, domains that lend themselves well to structured training modules. However, attitude is behavioural, psychological, and deeply contextual, especially in rural environments where social, cultural, and economic factors deeply influence individual motivation and risk behaviour.

While technical institutions, NGOs, and government agencies have scaled up skilling programs in rural areas, the absence of reliable frameworks to assess entrepreneurial attitude results in misdirected investments, high dropout rates, or business failures post-startup.

I believe that the right attitude matters more in rural entrepreneurship, or even entrepreneurship in general. Rural entrepreneurship has its unique challenges, like limited access to finance and markets, lack of required infrastructure, socio-cultural constraints, especially for women, and low institutional support. Here, it is the right attitude of the aspiring entrepreneur, which is a mix of persistence, opportunity-seeking, and resourcefulness, that becomes the decisive factor between failure and success.

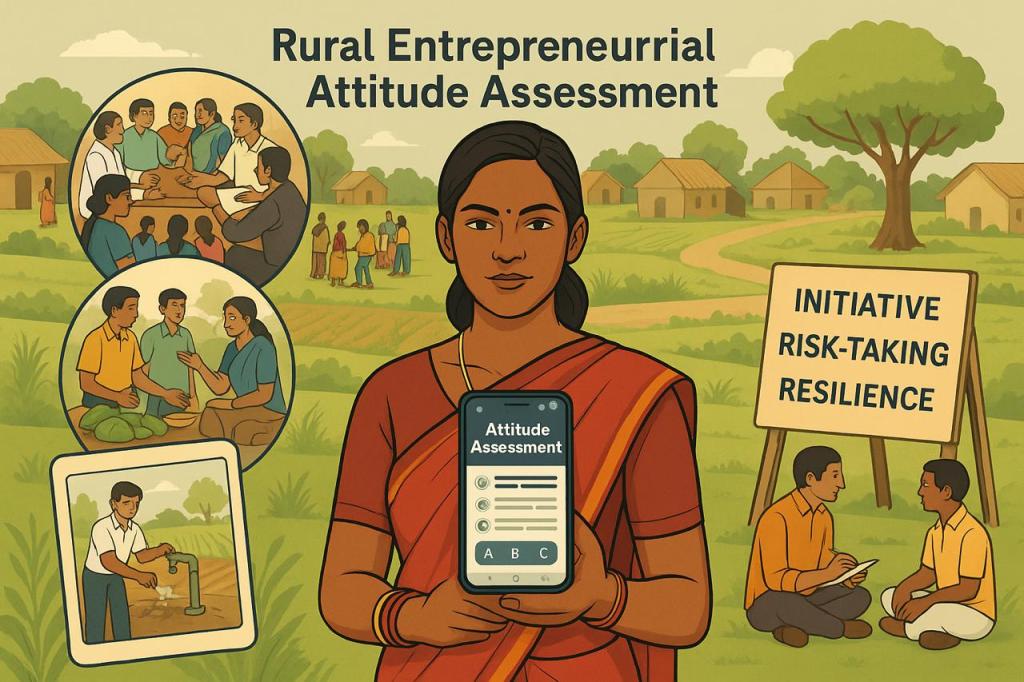

Current programs lack structured mechanisms to assess and nurture entrepreneurial attitude at the rural level, leading to inefficient selection of beneficiaries, poor resource utilization, and low sustainability of rural enterprises. Therefore, the critical question remains how we can measure the right entrepreneurial attitude in an aspiring entrepreneur at the rural level.

The challenge of evaluating attitude is not technical; it is conceptual. We must shift from a one-size-fits-all model to contextual diagnostics that honour rural reality. It is easy to dismiss a rural woman hesitant to speak in public as lacking “confidence.” But her daily navigation of caste norms, household labour, social conditioning, and budget constraints may reflect resilience and resourcefulness of the highest order.

What we must measure is not textbook confidence, but contextual courage. In my two decades of working with rural entrepreneurs in India, from tribal regions of the Northeastern states to drought-prone villages in Rajasthan, I’ve learned that talent is universal, but opportunity is not. Entrepreneurial attitude is not the privilege of the urban educated; it is often deeply embedded in rural lived experiences.

Our systems must develop culturally sensitive, grassroots-rooted, participatory frameworks to identify, not implant, an entrepreneurial attitude. Only then can we build truly inclusive ecosystems that tap into the latent power of rural changemakers. The future of rural entrepreneurship lies not in the replication of urban models but in recognizing and nurturing the indigenous spark. It is time we built tools that are beyond skills, to the spirit.

I am developing a framework and associated tools and metrics for measuring entrepreneurial attitude for inclusive rural enterprise development. I am calling it, “Rural Entrepreneurial Attitude Identification and Development (READ) Framework”. I will publish it as my next post.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not purport to reflect the views or opinions of any organization, foundation, CSR, non-profit or others.

The cover image is generated using Ai.