Economics is not about money

March 2, 2026 Leave a comment

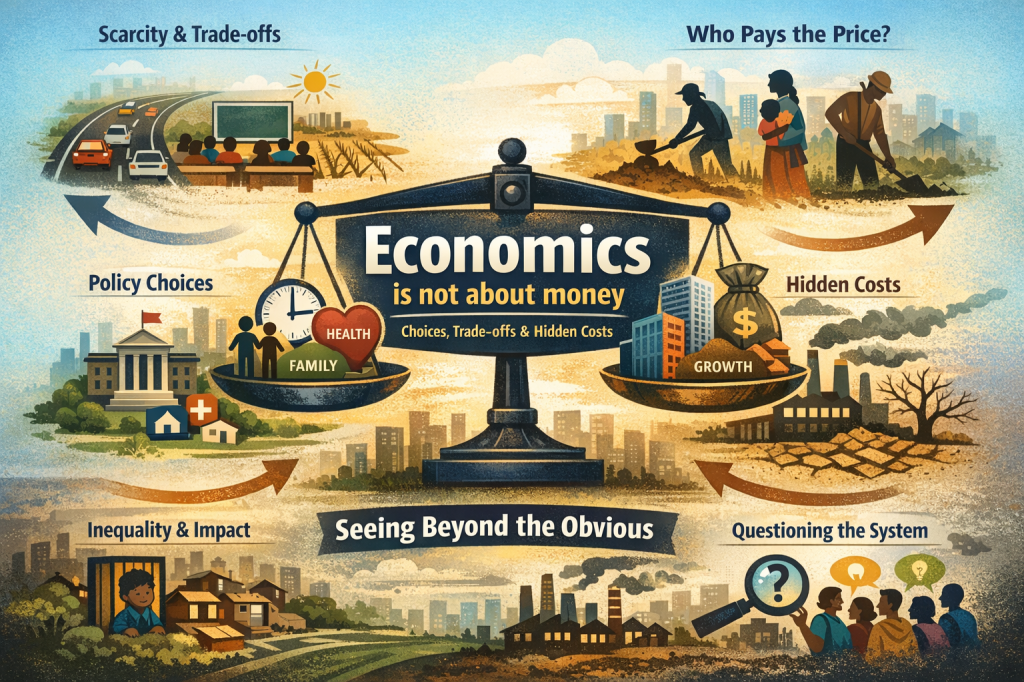

Most people think economics is about money, but it’s not. If it were, your life would make far more sense than it does. Economics begins much earlier than money, as it starts the moment you realise that you cannot have everything at once. You cannot have a high-paying job and abundant free time. You cannot have absolute security and complete freedom. You cannot say yes to every opportunity without saying no to something else. Economics is not about how much you earn, but what you give up for it. That invisible sacrifice, ‘what you could have done but didn’t, ‘ is the true currency of economics. We seldom talk about it, but it quietly shapes every decision we make.

Think of any random normal day of your life. You wake up earlier than you would like because traffic can be unpredictable. You scroll your phone while sipping morning tea, not because you want to, but because silence feels uncomfortable. You choose a quicker breakfast over a healthier one. You delay a difficult conversation at home. You tolerate a job you dislike because it pays the bills. None of these choices feels ‘economic.’ They feel personal. But every choice that you make is a trade-off. When you choose speed over health, comfort over honesty, income over meaning, you are doing economics. You are allocating scarce resources, such as time, energy, attention, and emotional capacity. Money enters later, as a convenient measuring tool, but the logic is already at work.

In India and several other similar developing countries, we live in a constant state of trade-offs. Long commutes to work steal hours from families. Overcrowded classrooms dilute learning. Low wages are compensated by the promise of stability. We accept these compromises so routinely that they stop feeling like choices at all and begin to feel like fate. Economics helps us see that they are not.

No matter how rich or poor you are, time is always in limited supply. A billionaire has the same twenty-four hours as a daily-wage worker. A student in Delhi and a farmer in Bihar both face limited days and uncertain futures. What differs is not scarcity itself but how it is managed and who bears its cost. Scarcity forces choices, which create trade-offs, and ultimately, trade-offs determine winners and losers.

If economics is about trade-offs, then the most important question is not about what we want, but what we are willing to give up, and who decides? This is where economics moves from being a personal lens to a political one. In democracies, these decisions are meant to be collective, negotiated through debate, budgets, and votes. When a government invests heavily in urban infrastructure but underfunds primary healthcare, it is not simply prioritising growth over welfare, but is choosing whose time matters. The commuter stuck in traffic benefits from a flyover, while the woman who walks kilometres to a hospital pays the price. These outcomes are often defended as efficiency, but efficiency for whom is rarely asked. Economics reminds us that aggregate gains can coexist with deep individual losses, and that averages hide pain as effectively as they reveal progress.

This way of thinking also changes how we view success. Growth figures, income levels, and productivity rates dominate economic conversations, but they measure outputs, not experiences. A country can grow richer while its people grow more anxious. A company can become more profitable while its workers burn out. A household can earn more while spending less time together. When we ignore these costs, we risk building systems that look successful on paper but feel unbearable in practice.

There is also a moral dimension to trade-offs that markets alone cannot resolve. Markets are excellent at responding to purchasing power, but often silent about need. They reward those who can pay, not those who suffer most. That is why leaving everything to ‘the market’ is itself a choice, one that often shifts costs onto the weakest. When clean air, safe housing, or quality education are treated purely as commodities, inequality is not an accident, but it is an outcome. Economics helps us see that fairness is not automatic, but must be designed.

This is the uncomfortable truth economics insists on. Every policy, every system, every personal decision benefits one and burdens someone else. There is no free lunch, only cleverly hidden bills. When a city prioritises flyovers over footpaths, it chooses cars over pedestrians. When an education system rewards rote learning, it sacrifices curiosity. When a company celebrates long working hours, it quietly taxes family life. These are not moral failures but are economic decisions. However, pretending they are natural or inevitable prevents us from questioning them.

The most dangerous costs are the ones we don’t notice. When an app is free, we assume there is no price. When a government scheme promises something for nothing, we rarely ask who is paying. When a product is cheap, we celebrate efficiency, not exploitation. But every benefit has a cost. If you don’t see it, it’s probably being paid by someone else, or even by your future self. Cheap food often means underpaid farmers. Free social media means monetised attention. Low taxes can mean broken public services. Fast growth can mean polluted air and exhausted bodies. Economics trains us to ask an unfashionable question: compared to what? Without this lens, we mistake convenience for progress.

At an individual level, thinking economically can be liberating. It replaces guilt with clarity. If you understand that your exhaustion is not just a personal failure but the result of incentives that reward overwork, you can begin to question those incentives. If you recognise that your inability to save is linked to rising living costs rather than laziness, you can demand better policies instead of harsher self-judgment. Awareness does not eliminate constraints, but it changes how we respond to them.

One of the quiet cruelties of modern life is how easily individuals are blamed for structural problems. If you are unemployed, you are told to upskill. If you are stressed, you are told to meditate. If you are poor, you are told to work harder. But you are rarely told to examine the system that made these outcomes likely in the first place. Economics reveals patterns where we see only personal failure. It shows how incentives shape behaviour, how power hides behind ‘market outcomes,’ and how rules written long ago continue to decide who gets ahead today. This does not absolve individuals of responsibility, but it does bring honesty to the conversation. You cannot fix what you refuse to name.

Economics is not about predicting stock prices or defending ideologies, but is more about clarity. About seeing how choices are shaped, how costs are distributed, and how power operates quietly through everyday decisions. You do not need equations to think economically. Instead, you need curiosity and courage to ask uncomfortable questions. And you need the humility to accept that every solution creates new problems. Once you start seeing life this way, it becomes difficult to unsee. You begin to notice the price tags on things that never claimed to be for sale, like time, trust, dignity, and attention. That awareness does not make life easier, but it makes it more honest. And honesty, in the long run, is the most valuable currency we have. When we see costs clearly, we can finally argue about whether they are worth paying, and whether the bill is being shared fairly. India is a masterclass in everyday economics. Families choose stability over passion, young people choose migration over belonging, villages trade environment for employment, and women trade ambition for safety. These are not random decisions but often are rational responses to constraints. When options are limited, even painful choices begin to make sense. Understanding this limitation is empowerment.

(Cover image is generated using AI)