The Whiteboard Mind

November 24, 2025 Leave a comment

In the age of digital tools, where every idea has a place in an app and every plan sits behind a login screen, the humble whiteboard continues to command its own quiet power. For many thinkers, creators, and problem-solvers, it remains the most dynamic canvas, a space where thoughts breathe, flow, and transform. For someone like me who designs projects, plans strategies, brainstorms ideas, and lead teams, the whiteboard and marker pen are not just tools. They are extensions of the mind, translating abstract thought into visible structure. It’s not nostalgia or resistance to technology; instead, it’s about harnessing a form of thinking that is visual, kinetic, and alive.

There’s a deep psychological connection between movement and cognition. When you draw or write by hand, especially on a large surface like a whiteboard, you activate a different mode of thinking. The body participates in the act of thought. The hand sketches a relationship, the eye follows it, the brain reinterprets it, and new connections emerge almost instinctively.

Typing or clicking on the keyboard keeps the mind linear, confined to lists, bullets, and boxes. But drawing on a whiteboard invites a non-linear form of exploration. You can start anywhere, a square, an arrow, a phrase, and the rest begins to grow organically. This freedom to expand, erase, and rearrange is what makes it such a powerful thinking process. Each line is a possibility. Every arrow, a hypothesis. And each erasure, a moment of learning. When thoughts become visible, they also become testable. A whiteboard externalises the inner dialogue of the mind. It takes ideas that could remain foggy abstractions and turns them into something you can point at, challenge, and reshape.

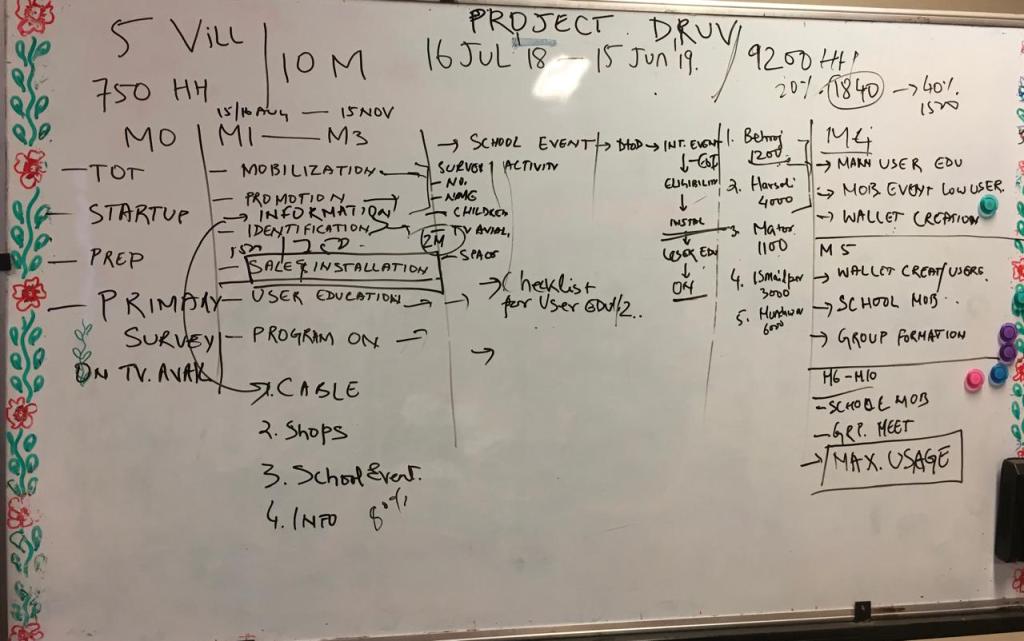

This visibility is particularly powerful in complex problem-solving or project design. When working through implementation challenges or building systems with multiple moving parts, you can literally ‘see’ the interactions. Causal diagrams, mind maps, and process flows make dependencies clear and highlight gaps that words alone might obscure. You can stand back and see the whole ecosystem, how resources connect, where bottlenecks might occur, or which variables influence outcomes. The whiteboard gives you that clear view while still allowing you to dive into details when needed. It’s thinking at both the macro and micro levels, which is simultaneously intuitive and analytical.

Every creative or strategic process begins in some form of chaos. Ideas compete, assumptions overlap, and clarity hides behind complexity. The whiteboard is where that chaos finds its first structure. Drawing mind maps is often the first step, not because they provide answers, but because they show relationships. From one central idea, branches grow, each representing a sub-theme, a factor, or an alternative. You can add, cross-link, or reframe them without fear of permanence. The visual form allows you to rearrange logic faster than your words can catch up.

Causal diagrams, in turn, help identify the forces at play of what leads to what, what influences what. In project planning, this is invaluable. You can trace dependencies between actions, timelines, or external conditions. You can see where interventions matter most. You can uncover loops, positive or negative, that either amplify progress or create recurring setbacks. In a sense, the whiteboard becomes a mirror of systems thinking. It holds complexity while keeping it human and accessible.

The whiteboard isn’t just a personal tool; it’s a shared language. I often use it in team meetings or group ideation sessions, as it turns abstract discussion into a collective visualisation. People see not only what is said, but how it connects. Misunderstandings surface faster because assumptions become visible. When everyone’s looking at the same diagram, they’re also looking at the same version of reality and not one filtered through individual interpretation.

It democratizes contribution, leading to one common understanding. A quiet team member can point at a link and ask, ‘Why does this connect here?’ or suggest a missing node. Visual representation invites curiosity and challenges hierarchy. It’s no longer about who talks the most, but about what the group sees together. Moreover, it encourages iteration. Unlike digital slides or documents that feel fixed, a whiteboard remains fluid. You can erase, redraw, and refine as the conversation evolves. Every stroke on the board is an act of co-creation. Even with PowerPoint presentations, I often end up on a whiteboard (if available) to explain concepts, flow, and possible results. It has proven to be an excellent tool for scenario visualisations.

There’s also the element of speed. With a marker in hand, you can think and draw at the pace of your thoughts. There’s no formatting, no tabs to open, no distractions from notifications or interfaces. When you’re solving implementation challenges or breaking down a project into actionable components, this speed matters. You can move from problem to hypothesis to possible solution in seconds. The visual rhythm keeps the momentum alive. And because it’s temporary and erasable, there’s less fear of getting it wrong. You can test a scenario, discard it, and move on. This low-cost experimentation fuels creativity and decision-making alike. In fact, the transient nature of a whiteboard is part of its strength. It reminds you that ideas are living entities to be evolved, not preserved.

When designing projects, a whiteboard allows for holistic structuring. You can begin with purpose at the centre, draw out stakeholders, resources, activities, and outcomes, and gradually watch a project take shape like a constellation. At this stage, aesthetics and functionality merge. The diagram is not just a record; it’s a design prototype. You can visualise workflows, timelines, partnerships, and even behavioural change models. Seeing everything laid out helps identify what’s missing and what’s redundant. For ideation, it’s even more liberating. The blank board is an invitation to explore. You might start sketching something unrelated, only to stumble upon an insight that reframes the entire problem. The act of drawing keeps your attention anchored and your imagination open.

Often, my Millennial and Gen Z associates argue that digital whiteboards and collaboration tools replicate all these benefits, but there’s something irreplaceable about standing in front of a board with a marker. Your posture changes, your mind sharpens. The body’s movement through space, stepping back to observe, leaning in to draw, engages multiple senses. It’s immersive in a way screens can’t replicate. A whiteboard has boundaries, forcing you to prioritise. What fits stays, and what doesn’t must be distilled. This physical constraint often leads to conceptual clarity. Maybe the old school professor in me has a bias!

Using a whiteboard and marker isn’t about rejecting modern tools; it’s about complementing them. Digital systems store and polish. Whiteboards create and provoke. For anyone who works on complex projects, leads teams, or solves multidimensional challenges, the whiteboard offers a cognitive advantage as it makes thinking tangible. It transforms abstract reasoning into something you can walk around, discuss, and reshape. It reminds us that clarity isn’t found inside the mind alone; it’s constructed through visible relationships and shared understanding.

For me, the whiteboard is more than a surface; it’s been my live, on-the-spot thinking companion. Every mark carries curiosity; every erasure, humility. It captures not just what we know, but how we learn. To think with a whiteboard is to think in motion. It’s a dialogue between mind, hand, and idea. It’s where chaos meets order, and where clarity emerges, not from control, but from exploration. In a world of digital efficiency, perhaps the most human form of innovation still begins with a marker, a blank board, and the courage to draw what we don’t yet fully understand.

(The cover photo is from a project planning session by me; the central photo is generated using AI)