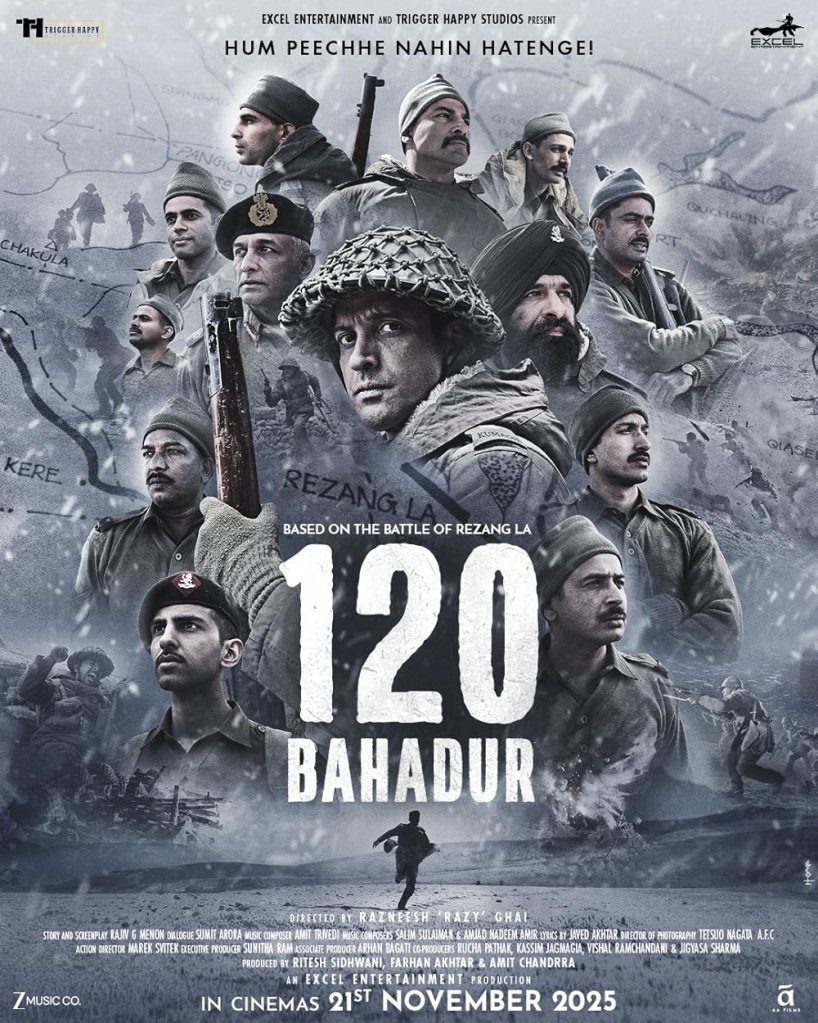

120 Bahadur

January 12, 2026 Leave a comment

Genre: War Drama | Year: 2025 | Duration: 160 mins | Director: Razneesh Ghai| Medium: Theatre (PVR Cinemas) | Trailer: HERE | Language: Hindi | Cast: Farhan Akhtar, Raashil Khanna, and others | My rating: 3.5/5

Favourite Dialogue: “Unka khoon uss mitti mein zaroor milega sahab, aur jo khoon milega who unki chhaati ka hoga peeth ka nahi”

120 Bahadur is based on the real-life sacrifice of the 120 soldiers of Charlie Company, 13 Kumaon Regiment of the Indian Army at the Battle of Rezang La during the 1962 Sino-Indian War. It chronicles the extraordinary courage of 120 Indian soldiers who stood their ground against 3000 Chinese troops. The film focuses on Major Shaitan Singh Bhati (played by Farhan Akhtar), showcasing the grit, sacrifice, and valour of soldiers fighting in the brutal cold and high altitude of Ladakh. The story is narrated through the memories of a surviving soldier, and it unfolds as a tribute to the heroism of a band of brothers whose courage came at the highest cost.

The film’s strongest suit is its war sequences and immersive realism. The battle sequences at Rezang La, rifle fire, bayonet charges, final close-quarters combat, the harsh terrain, bone-chilling cold, and the almost claustrophobic desperation when ammunition runs out are realised with a fierce intensity that’s rare for many modern Hindi war films. The film features brilliant cinematography by Tetsuo Nagata, with breathtaking shots of snow-covered mountains, freezing desolation, and the starkness of high-altitude warfare. The film mostly avoids glorifying war for its own sake and is a sober portrayal of the events. This sincerity gives the film humility as it doesn’t frame itself as a triumphant spectacle, but a respectful tribute and remembrance.

Farhan Akhtar delivers a thoughtful performance. He largely avoids the larger-than-life histrionics often associated with Bollywood war heroes. Instead, he feels rooted, authoritative yet human, decisive yet burdened. At the same time, the supporting cast, many of them lesser-known actors, bring the infantrymen to life with grit, camaraderie, humour, and vulnerability. Their messy friendships, small conversations, homesickness, and occasional fears humanise what might otherwise have been just a war drama with guns and trenches.

However, the film seemed to have weak character development; their individual stories were barely sketched out. This makes certain deaths feel less impactful emotionally, more like casualties on a battlefield than deeply personal losses. Because of that, while the collective sacrifice hits home, personal grief and tragedy often don’t. The film’s narrative isn’t always smooth, as flashbacks to family life, interspersed with the lead-up to battle, sometimes break the tension. The prelude drags at times, and the buildup to the climax lacks the steady escalation that such stories need for maximum impact.

I felt that the depiction of Chinese soldiers has been overly simplified and tends to lean towards caricature: monolithic, villainous, almost cartoonish, robbing them of nuance or complexity. This weakens the moral weight of the conflict and reduces it to a binary ‘good vs evil’ war movie. In parts, storytelling relies heavily on familiar Bollywood popular drama of last-minute motivational speeches, montage-heavy sequences, formula flashbacks and emotional beats, which keep the film from feeling fully original.

120 Bahadur is not a perfect film, but it is an earnest, important one. It doesn’t glamourise war, and it doesn’t demand you leave the theatre cheering mindlessly. Instead, it makes you reflect on duty, courage, and sacrifice. As a cinematic recreation of a tragic but heroic moment in India’s history, the film succeeds more often than it fails. Its war sequences are unflinching and immersive; its portrayal of brotherhood and sacrifice is heartfelt; its lead performance is measured and credible.

But beneath the combat and solemn patriotism, it made me think that India’s rural society holds the backbone of India’s defence forces. The film also has a sociological moment where rural identity, class, caste, and nationhood intersect. The men of Charlie Company came largely from agrarian communities, especially the Ahir (Yadav) belt of Haryana and Western UP. Their lives before the war were shaped by farming cycles, monsoon anxieties, livestock, joint families, and deeply rooted village cultures. The film becomes a testament to how rural young men, in search of dignity, livelihood, and service, become the face of national defence but rarely the face of national storytelling.

Despite its narrative shortcomings, 120 Bahadur performs a cultural service of returning Rezang La to public consciousness.