Empowered, yet edited

February 16, 2026 Leave a comment

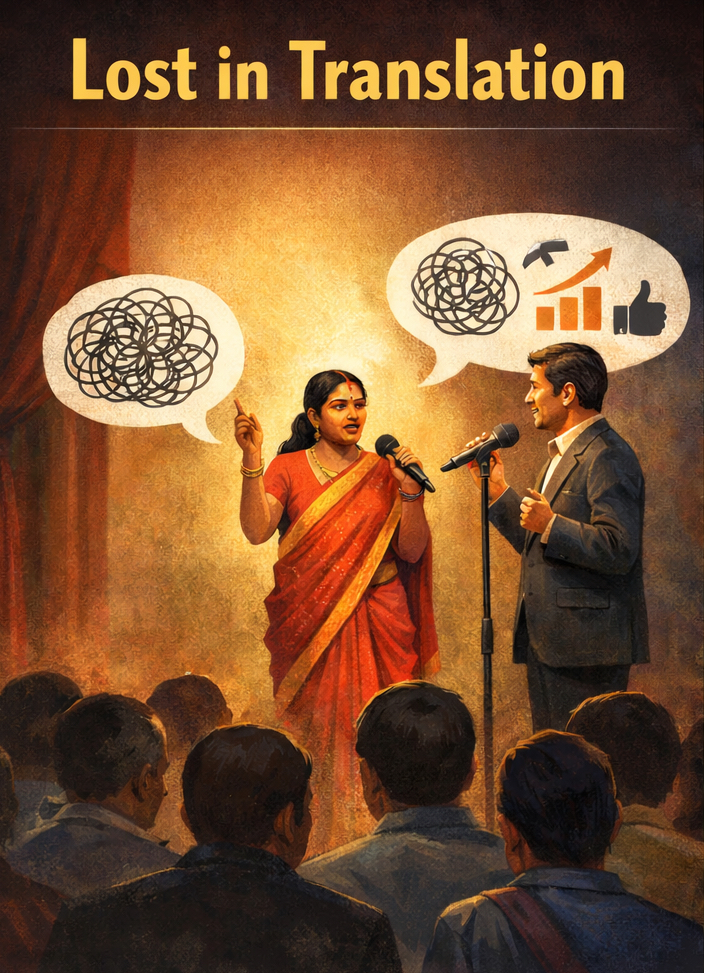

At a recent social impact conference that I attended, a woman from a village in Gujarat took the stage to share her success story. She spoke in Gujarati, her native language, addressing an audience that mostly did not understand her language. To bridge this gap, an educated, articulate, and well-positioned man was tasked with translating her words into Hindi. What followed was not a simple act of linguistic mediation but a revealing demonstration of how women’s agency is often compromised, even in spaces that claim to celebrate their empowerment. The translator did not translate her speech faithfully, and instead, he offered a compressed interpretation, presenting what he believed to be the ‘gist.’ Sensing that her meaning was being altered, the woman interjected repeatedly, attempting to reclaim her narrative. This was not a one-off, and I have witnessed this often at several conferences and during multi-stakeholder field visits to villages.

This moment captures a broader and deep-rooted pattern. Translation is rarely a neutral act, and it is more like an exercise of power. The person who translates decides what matters, what can be omitted, and what should be softened or sharpened. When men translate for rural women who are less formally educated, speaking to urban or elite audiences, they often filter lived experience through institutional and patriarchal lenses. Emotion becomes excess, complexity becomes confusion, and struggle is smoothed into success. In the process, women’s narratives are made more palatable but less truthful. What the audience receives is not the woman’s voice, but a curated version shaped by male interpretation.

The woman’s interjections were particularly instructive. Her repeated attempts to stop the translator were efforts to assert control over her own story. A man interrupting to ‘clarify’ is viewed as confident and authoritative, while a woman interrupting to reclaim her meaning is seen as difficult or ungrateful. This double standard reflects a long-standing patriarchal belief that women are unreliable narrators of their own lives and that male mediation is both necessary and superior. The conference scene I described is simply a contemporary indicator of this enduring injustice.

There is also a fundamental difference between how women often choose to speak and how men often interpret. Women from marginalised contexts tend to narrate their lives through stories that are relational, nonlinear, and emotionally textured. They speak of collective effort, ongoing uncertainty, unpaid labour, and the fragility that coexists with success. Male interpreters, shaped by institutional norms, often prioritise outcomes, efficiency, and coherence. In translation, vulnerability is trimmed away, contradictions are resolved, and struggle is reframed as triumph. This is not a harmless simplification; rather, it is an injustice that strips women’s knowledge of its depth and political significance.

The quest for gender equity requires more than symbolic representation. It demands that women retain control over their narratives, including how they are translated and transmitted. This means valuing verbatim translation over interpretation, and creating spaces where speech is not rushed or sanitised. It also requires a cultural shift in how interruptions are understood. When a woman interrupts a translator, it should be recognised as an assertion of dignity and agency, not as a breach of decorum. Gender justice is not achieved by merely giving women a mic, but will only be achieved when their words are allowed to travel without being reshaped by male authority. Until then, even the most empowered women will remain vulnerable to having their voices lost—not in silence, but in translation.

(Cover image is created using AI)

(Disclaimer: The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not purport to reflect the views or opinions of any organisation, foundation, CSR, non-profit or others.)